research

summary

Diagnosis

of Alzheimer’s disease should be made as

accurately and early as possible. The more severe symptoms of

Alzheimer’s

disease can be delayed using medication, but this delay is much more

efficient

in people who are in the early stages of the disease (Giacobini, 2000).

There

is also evidence that people in the pre- or early diagnosis stages are

more

likely to benefit from rehabilitation (Clare, Woods, Moniz-Cook, Orrell

&

Spector, 2005). It is also crucial to have a way of assessing the

impact on

cognitive abilities of Alzheimer’s disease progression, and

of any

pharmacological or other therapies. This means that it is essential to

have a

diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease as accurately and early as

possible.

Memory

problems are the central symptom of

Alzheimer’s disease. Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease

on the basis of memory

difficulties alone, however, is problematic. This is because memory

difficulties are not specific to Alzheimer’s disease. They

are also a common

feature of healthy ageing and can be caused by a number of disorders.

Research

by our group and colleagues has shown that

people with Alzheimer’s disease have significant difficulties

doing two things

at once: ‘dual-tasking’. Healthy older adults do

not demonstrate any difficulty

dual-tasking. This dual-task impairment, therefore, may be specific to

Alzheimer’s disease.

We are

now trying to convert our research tools into

a clinical assessment, and ensure that these results are sensitive and

specific

to Alzheimer’s disease. After this, we hope that this tool

will be used by GPs,

psychiatrists, psychologists and neurologists to assist diagnosis of

Alzheimer’s disease and allow follow up studies to check

whether treatments are

effective.

what is dual-tasking?

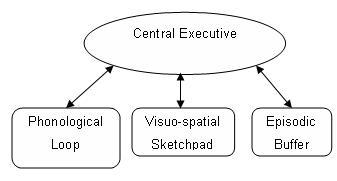

It is thought that

dual-tasking, the

ability to do

two things at once, is a product of the brain’s ability to

coordinate. We

understand this dual-task coordination to be part of ‘working

memory’. In 1974, scientists Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch

proposed that short-term memory

should be thought of as ‘working memory’, which can

store

and maintain a

certain amount of information temporarily. Information may be

phonological

(sounds/language) or visuo-spatial (vision/space). Phonological

information,

such as a friend’s telephone number, is handled by the

‘phonological loop’ and

visuo-spatial information, such as the route you would plan to take to

go to

your friend’s house, is handled by the

‘visuo-spatial

sketchpad’.

Phonological

and visuo-spatial information can be

integrated to form a memory. This is done by the ‘episodic

buffer’. These three

‘slave’ systems: the phonological loop,

the visuo-spatial sketchpad and

the episodic buffer, are co-ordinated by the ‘central

executive’:

Baddeley’s (2000) Model

of Working Memory

When we

do two things at once, such as walking and

talking, Baddeley’s (2000) model of working memory suggests

that the central

executive has to coordinate the phonological loop and visuo-spatial

sketchpad

slave systems for successful performance of these two concurrent

activities. It

is therefore proposed that central executive dysfunction can cause

dual-task

impairment, as seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

what

happens to dual-tasking

ability in alzheimer’s disease?

In

1986, Baddeley, Logie, Bressi, Della Sala and Spinnler reported that

people

with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) demonstrate a selective

impairment in

dual-tasking. They based their conclusions on studies comparing people

with AD

with healthy young and older adults, performing two tasks at once: a

tracking

task as well as an articulatory suppression, simple reaction time to

tone or

auditory digit span task. They found that when tracking was paired with

simple

reaction time or digit span task (but not articulatory suppression),

the people

with AD performed dramatically lower than the healthy young or older

adults.

This effect remained even when the difficulty of the tracking task, and

the

length of digit span were adjusted, so as to equate performance across

the

three groups when the tasks were performed alone. The group

hypothesised that

this effect was not seen when the tracking task was paired with the

articulatory suppression task because it was not sufficiently demanding

to

require the participant to dual-task.

Some

suggested, however, that the findings in the Baddeley et al. (1986)

study could

have been caused by information overload. Thus, Baddeley, Bressi, Della

Sala,

Logie and Spinnler (1991) did a follow-up study of the same

participants,

assessing their ability to dual task when the level of difficulty of

the two

tasks was adjusted. They suggested that should the cause of the

impairment be

due to overload, there should be greater difficulty across all tasks:

single or

dual, when task difficulty was increased. They found, however, that

there was

further decrement in performance in the dual-task condition only.

Furthermore,

they found that there was no tendency for more difficult single tasks

to show

greater sensitivity to the progression of the disease.

These experiments and findings

suggest that that AD features a specific impairment in

the central executive. Further research has found that dual-task

performance correlates with the presence of behavioural problems

(Baddeley, Della Sala, Papagno & Spinnler, 1997b) and

difficulties

in people with AD performing everyday tasks that require

dual-tasking, such as keeping track of conversations (Alberoni,

Baddeley, Della Sala, Logie & Spinnler, 1992) or talking while

walking (Cocchini, Della Sala, Logie, Pagani, Sacco & Spinnler,

2004).

how can this be developed into a

clinical tool?

Currently, assessments

of memory functioning are

thought to be the most useful tests to detect AD. These tests are very

sensitive to AD, but unfortunately as memory difficulties can be

present in

many other types of disorders and even in normal ageing, these tests

are not

specific to AD. This can lead to diagnostic uncertainty, worrying for

both

patient and significant others, or worse, incorrect diagnosis of AD.

These

tests, therefore, require further components to improve their

specificity.

Previous

research revealed that when single task

difficulty was equated across groups, people with AD have difficulty

dual-tasking,

but younger and older healthy adults do not (Logie, Cocchini, Della

Sala &

Baddeley, 2004). Moreover, difficulty dual-tasking worsens as the

disease

progresses; whereas the ability to do either of the two tasks alone

deteriorates much less dramatically (Baddeley, Bressi, Della Sala,

Logie &

Spinnler, 1991). Furthermore, this dual-tasking impairment has been

found to

exist across a range of different combinations of tasks (Logie et al.,

2004).

The assessment of dual-task ability, therefore, may be an excellent way

of improving

the specificity of AD diagnosis.

A

paper and pencil version was developed, which has been piloted and

found to generate the same results as the laboratory version (Baddeley,

Della Sala, Gray,

Papagno & Spinnler,1997a; Della Sala, Baddeley, Papagno

&

Spinnler, 1995), but this version is not yet ready for

widespread clinical use. Firstly, a sensitive assessment procedure must

be

established; secondly, a larger study assessing group differences must

be

conducted; and thirdly its specificity across a wider range of

disorders must

be assessed. This current project, funded by the Alzheimer’s

Society, aims to

develop a valid and reliable test of dual-tasking ability, which is

sensitive

and specific to Alzheimer’s disease.

references

|

Alberoni,

M., Baddeley, A., Della Sala, S., Logie, R. H. & Spinnler, H.

(1992). Keeping track of a conversation: Impairments in

Alzheimer's

disease. International

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 7, 639-646. |

|

Baddeley,

A. D. & Hitch, G. J. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower

(Ed.), The

psychology of learning and motivation

(Vol. 8; pp 47 - 89). London:

Academic Press. |

|

Baddeley, A. D, Bressi, S.,

Della Sala, S., Logie, R. H. & Spinnler, H. (1991). The decline

in working memory in Alzheimer’s

disease: A longitudinal study. Brain, 114,

2521 – 2542. |

|

Baddeley, A., Della Sala, S.,

Gray, C., Papagno, C.,

& Spinnler, H. (1997a). Testing central executive functioning

with a

pencil-and-paper test. In P. Rabbitt (Ed.), Methodology

of frontal and executive function (pp. 61 -

80). Hove: Psychology Press. |

|

Baddeley, A., Della Sala, S.,

Papagno, C.,

& Spinnler, H. (1997b). Dual-task performance in dysexecutive

and nondysexecutive patients with a

frontal lesion.

Neuropsychology, 11, 187-194. |

|

Baddeley, A. D., Logie, R.,

Bressi, S., Della Sala, S., & Spinnler, H. (1986). Dementia and

working memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental

Psychology, 38A, 603-618. |

|

Clare, L., Woods, B.,

Moniz-Cook, E., Orrell, M. & Spector, A. (2005). Cognitive

rehabilitation interventions targeting

memory functioning in

early-stage Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.

Systematic review.

Cochrane Library. |

|

Cocchini,

G, Della Sala, S.,

Logie, R. H., Pagani, R., Sacco, L. & Spinnler, H. (2004). Dual

task effects of walking

while talking in

alkzheimer disease. Revue

Neurologique, 160, 74-80. |

|

Della

Sala, S., Baddeley, A.,

Papagno, C. & Spinnler, H. (1995). Dual task paradigm: A means

to

examine the central executive. In J. Grafman, K.

J.

Holyoak, F. Boller (Eds.). Structure

and functions of the human prefrontal cortex. Vol. 769.

New York: Annals of the New

York Academy of Sciences, pp. 161-171. |

|

Giacobini,

E. (2000).

Cholinesterase inhibitors stabilize Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy

of Sciences, 920,

321 – 327. |

|

Logie,

R.H., Cocchini, G., Della

Sala, S. & Baddeley, A.D. (2004). Is

there a specific executive capacity for dual task

co-ordination? Evidence from

Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropsychology

18,

504-513. |